Due to the time of clergy transition currently being undergone by the Church of the Saviour, Two Crabapples will not publish new content for a time. Please feel free to browse the archives for an encouraging word.

Sunday, May 19, 2013

Two Crabapples Hiatus

Due to the time of clergy transition currently being undergone by the Church of the Saviour, Two Crabapples will not publish new content for a time. Please feel free to browse the archives for an encouraging word.

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Who Runs Toward and Injury?

During Louisville's Elite Eight win over Duke, on their way to a National Championship, Kevin Ware experienced what is probably the most gruesome injury ever broadcast on live television. If you were watching, you'll know what I'm talking about, and if you weren't...there's really no way to describe it. It will suffice to say that broken bone was visible through skin, and men young and old were immediately moved to tears at the sight. Everyone, coaches, players, and referees, instinctively moved away from Ware, horrified by his injury. Only one person, Ware's Louisville teammate Luke Hancock, went the other way. Here's a description of what happened next, from Grantland's Shane Ryan:

But after turning his head with everyone else at the sight of the snapped bone, Luke Hancock was the one who came to Ware's side and gripped his hand. He said a prayer, guided him through the initial trauma, and stayed with him on the floor while the medical staff worked. It was because of Hancock, at least in part, that Ware overcame his initial horror and encouraged his teammates to keep playing, to win the game.

In the days leading up to Louisville's Final Four game against Wichita State, the question Hancock faced over and over was why he'd done it. Why did he have the presence of mind to react the way he did?

When he answered the question Friday in the Georgia Dome's media center, he probably could have recited a response from memory. He'd been the centerpiece of hundreds of stories for that one act, and was destined to be featured in a hundred more. Which is why it surprised me that his answer, simple as it was, still moved me.

"You know, I don't really know why I went out there," he said. "But, you know, I just didn't want him to be alone out there. I don't know."

Hancock, by some miracle (note that he says, even after having days to think about it, that he doesn't know why he went to Ware's side), was moved to go toward the grisly injury, rather than away from it. Though Luke Hancock is in no way Jesus Christ, this direction of movement is indeed Christlike.

Here's St. Paul, theologizing Luke Hancock:

You see, at just the right time, when we were still powerless, Christ died for the ungodly. Very rarely will anyone die for a righteous person, though for a good person someone might possibly dare to die. But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us (Romans 5:6-8).

God made him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God (2 Cor. 5:21).

When the uninjured (righteous) goes toward the injured (unrighteous), miracles happen. When Christ comes toward us, even as we lie there, broken in sin, that miracle is our salvation.

Wednesday, April 17, 2013

Grace From the Very Top

1993 is, I'm sure, notable for many things. But for some, it was most notable as the year of the second straight "Fab Five" appearance in the NCAA National Championship game. The year before, Jalen Rose, Juwan Howard, Jimmy King, Ray Jackson, and Chris Webber had become famous for being an all-freshman starting five at the University of Michigan, introducing what has been referred to as "a hip-hop element" into the game, and getting all the way to the championship game before losing to Duke. The next year, as sophomores, the Fab Five was even better. Again, they went all the way to the championship, this time against North Carolina.

And then, the timeout happened.

Very late in a close game, Chris Webber (the team's best player and the man who would be drafted first overall in the upcoming NBA draft) called a timeout when his team didn't have one. Such a mistake results in a technical foul, giving the opposing team two free throws and the ball. Michigan couldn't recover, and lost. Webber was ruthlessly mocked, both at the time and for years to come. A perennial All-Star, "Chris Webber timeout" is still the first Google suggestion when you type in his name.

A few days after that fateful game, though, Chris Webber got a letter (you can even see the handwritten version HERE):

I have been thinking of you a lot since I sat glued to the TV during the championship game. I know that there may be nothing I or anyone else can say to ease the pain and disappointment of what happened. Still, for whatever it's worth, you, and your team, were terrific. And part of playing for high stakes under great pressure is the constant risk of mental error. I know. I have lost two political races and made countless mistakes over the last twenty years. What matters is the intensity, integrity, and courage you bring to the effort. That is certainly what you have done. You can always regret what occurred but don't let it get you down or take away the satisfaction of what you have accomplished. You have a great future. Hang in there.

Sincerely, Bill ClintonChris Webber did have a great future, and though I suspect he's never totally gotten over that moment in 1993, this letter must have been, and likely continues to be, an incredible balm for the wound. Such is the inevitable operation of grace in the face of the world's judgment.

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

Tiger Woods: Theologian of Glory

Tiger Woods' new ad campaign (or, more accurately, Nike's new ad campaign featuring Tiger Woods) is making the rounds. Featuring Woods staring down a put, the tagline is "Winning Takes Care of Everything," a quote attributed to "Tiger Woods, World #1." There has been much debate about the taste level of this ad, seeing as how Tiger Woods remains a divorcee with less than full custody of his children. Has "everything" really been taken care of? Is this an appropriate message to be sending to children?

The great Gerhard Forde (via the greater Martin Luther) talked about this idea, that victory heals all wounds, in his seminal On Being a Theologian of the Cross. Here's a taste:

Indeed, so seductive has the exiled soul myth been throughout history that the biblical story itself has been taken into captivity by it. The biblical story of the fall has tended to become a variation on the theme of the exiled soul. The unbiblical notion of a fall is already a clue to that. Adam originally pure in soul, either by nature or by the added gift of grace was tempted by baser lusts and "fell," losing grace and drawing all his progeny with him into a "mass of perdition." Reparation must be made, grace restored, and purging carried out so that return to glory is possible. The cross, of course, can be quite neatly assimilated into the story as the reparation that makes the return possible. And there we have a tightly woven theology of glory! (p. 6)Tiger Woods was nothing if not an "exiled soul" (Forde, it should be noted, takes this chilling term from the philosopher Paul Ricoeur). Reparation needed to be made, and the Nike ad claims that "winning" was the route. Forde's claim is that Christianity all too often uses this same "exiled soul" story (he calls it "the glory story") and simply puts the cross in place of victories on the golf course. Still, though, it is "success," in one form or another, that is required for us to regain our former stature.

Woods' ad posits a thing that you can do to regain your purity: win. Christianity, as it is often practiced, posits something, too: word hard, pray hard, be righteous, and you can regain that close relationship with God that your sinful life cost you. On the golf course, a theology of glory can work in the short term: win, and the accolades will come back. The money will come back. The sponsors will come back. Even the beautiful women will come back. But where your "exiled soul" is concerned? It is only the victory (ironically, through death) of another, freely given to you, that can offer new life.

Tiger Woods' life isn't new...it's merely buffed clean until new cracks appear (or until he starts losing again). We require something more permanent, something that will give us peace. Admonition ("Go win!") won't do it. Only a gift will do. "Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!" (Romans 7:25)

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Don't Hate Mike Piazza, You Are Mike Piazza

Mike Piazza's autobiography is called Long Shot, and reviewer Rob Neyer thinks it's a long shot that anyone will really like the book. Neyer does admit that the book "semi-obsessed" him for a week. He claims to be unsure of the reason, despite the well-written nature of the piece, but suspects that it has something to do with the book being "a case study in narcissism."

Neyer writes of Piazza's book, before saying that he "can't really recommend [it] to readers":

He really wants you to think he was a great hitter. Piazza hit 427 home runs in his career, and he mentions something like a hundred of them. He's got the record for the most home runs by a catcher. And right after the section where he talks about breaking the old record, he launches into an extended discourse about what a great player he was. Like he's trying to convince us, yes ... but also as if maybe he's trying to convince himself.

He really wants us to think...that beautiful women -- Playboy models mostly, and Baywatch actresses -- find him incredibly appealing. I wish the otherwise-estimable index listed mentions of "Playmate", "Baywatch", and "actress". But there are a lot of them in there. And when relating how he met his future wife Alicia, he simply describes her as "a Baywatch actress, and a former playmate, to boot."I know why Neyer finds Mike Piazza's "case study in narcissism" uncomfortable and impossible to recommend: Rob Neyer is a narcissist! Now, I don't say that because I know Rob Neyer, or because I've found Neyer's work to be narcissistic. In fact, far from it. For any baseball fans out there, Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Legends: The Truth, the Lies, and Everything Else is a fascinating (and non-narcissistic) read. I know that Rob Neyer is a narcissist because I am a narcissist. And so are you.

The estimable Paul Zahl once scoffed in a seminary class at the idea that there should be such a thing as "Narcissistic Personality Disorder." His claim was that, if such a thing did exist, every human being should be immediately diagnosed with it. If I discovered that Playmates and Baywatch actresses found me attractive, I'd rent ad space on the side of Mt. Everest to announce it to the world. If I'd hit 427 home runs in a successful major league career, I might write an autobiography for each one of them. Of course, these things haven't happened to me. But that doesn't stop me from desperately wanting you to think that I'm a good writer, a deep thinker, funny, and, you know...maybe at least a little attractive? No? Not even a little? Okay, let's move on.

We find the narcissism of others uncomfortable because we fear that it might shine a light on our own, like Ed Norton in Fight Club, who worries that Helena Bonham Carter's support-group fakery will out him as a faker, too. Underneath (but not too far underneath!) it all, we have a caustic narcissist who champs at the bit of social convention. We know it's not okay to appear narcissistic, so we keep the little guy chained up.

Better, though, to call a thing what it is. We desperately search for the affirmation of others (whether for our athletic prowess, physical attractiveness (still nothing?), or devastating wit) due to our (usually appropriate) fear that our weakness, ugliness, and banality are obvious to all. In other words, we are sinners looking for someone -- anyone! -- to tell us that we're not. We're looking for someone to save us without our having to die. As billionaire and amateur theologian Dan Gilbert once noted, it doesn't work that way. For resurrection to occur, there must first be a death. We must admit to our faults, allow Jesus to put the narcissist inside us beside him on the cross, and be raised to a new life of peace.

You know, maybe it's in that new life that a Playmate will find me attractive.

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

Even Jim Valvano Died

Jim Valvano (most likely known to non-sports fans as the namesake of the Jimmy V Foundation, a cancer research supporter which has given away hundreds of millions of dollars to fight the disease) was the subject of the latest ESPN 30-for-30 documentary, "Survive and Advance," which premiered on Sunday night. The doc is about the unlikely path-to-a-championship of the 1983 North Carolina State Wolfpack, coached by Valvano, which included nine consecutive must-win games, many of which came down to the final seconds. The team's run (the final basket in the championship game was recognized by Sports Illustrated and ESPN as the "greatest moment in the history of college basketball) was fascinating, but also typical, in a Disney film sort of way. It played out in exactly the way Michael Eisner might have recommended. What's interesting to me is how the documentary treats Valvano's illness and eventual death.

Naturally, Valvano's diagnosis, foundation-founding, and death are a major part of this story. Jonathan Hock, the director, has said that one of the things that interested him most about this story was that it was a wonderful tale of triumph after triumph being told about the life of "a doomed man."

Interviewee after interviewee (Valvano's players, wife, and friends, which include such luminaries as Mike Krzyzewski, Dick Vitale and Sonny Vaccaro) told of how, when Valvano was diagnosed with cancer, they thought -- no, they assumed -- that he'd "beat it." This is the language we use with cancer: the language of victory. I saw a post on Facebook recently in which a young boy wanted 100,000 "likes" because he'd "beaten" cancer. Valvano's friends all spoke of being shocked as he became sicker, and ultimately astonished at his death. They'd thought he would win.

Even Jim Valvano died. The consummate winner didn't win. The Facebook boy might have beaten cancer, but he hasn't beaten death. No one has, or ever will. Well, except this one guy.

As humans, our most desperate wish is to win. We try to win everything, up to and including the ultimate contest: us against our own deaths. The profundity of the cross is that it looks death in the face and confronts it directly. The cross is the end of the human contest. We lose. Even Jim Valvano lost. No one "survives and advances."

God, in Christ, brings victory out of defeat. God, in Christ, brings life out of death. We all die, but in Christ, we have the hope -- no, the promise -- of new and eternal life.

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Can You Boo a Player to Greatness?

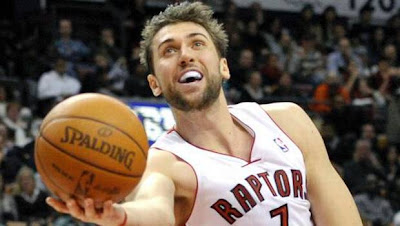

The Toronto Raptors' Andrea Bargnani, the number 1 overall pick in the 2006 NBA Draft, is having a terrible season. So terrible, in fact, that he's being loudly booed by his home fans. Check out this quote from Zach Lowe of Grantland.com: "Bargnani has been obscenely horrible on both ends since his return from injury, to the point that [head coach] Dwane Casey is sneaking him into home games after timeouts so that fans don't have a chance to boo the Italian big man at the scorer's table." Bargnani's case is certainly not unique; under-performing players are often booed at home. What's most interesting, though, is a question: does the strategy work?

In theory, home fans boo their own players to shame them into working harder. Some, of course, might be expressing simple hatred, but I think that most fans would prefer that their players actually play well. So let's take a quick look at Bargnani's stats: He's shooting 47% from the field on the road (which is pretty bad for a man of Bargnani's size, though he is a perimeter player)...and an absolutely horrific 30% at home. Thirty percent! Obscenely horrible indeed.

St. Paul said that "the law was brought in so that the trespass might increase" (Romans 5:20). There can be no clearer evidence than Andrea Bargnani. He's playing terribly. Subjected to the law, the chorus of boos that tells him he's not good enough, Bargnani is significantly worse. The law comes in; the trespass increases. The more Bargnani is reminded of how terrible he is, the more terrible he becomes. The same is true of every one of us.

Christians have an outlet that Bargnani lacks: when we hit bottom, we have a savior there to pick up the pieces. A Christ who substitutes his perfection for our failure. The more shots Bargnani misses, the more likely he is to be out of a job. The more we fail, the more likely we are to call out for that savior.

So what are we left with? Does the strategy work? Well, yes and no. The application of the law doesn't work, at all. Those who are oppressed perform significantly worse than they do otherwise. The law, remember, was brought in so that the trespass might increase. But for the Christian? The law works, absolutely. Paul again: "Therefore no one will be declared righteous in God’s sight by the works of the law; rather, through the law we become conscious of our sin" (Romans 3:20).

We think that the law will coax life out of sickness, or a made jumper out of Andrea Bargnani. It doesn't work, but it will kill. The law's true work is to destroy, to remind us of our failure. Thank God we have a savior, the Christ who brings life out of death. I wonder what would happen if Raptors fans cheered Andrea Bargnani when he came into the game, as our God cheers us who are covered by Christ's righteousness. It'd be something to see.

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

Choosing Your Own Adventure Ain't What it Used to Be

In his AV Club "Memory Wipe" article on "Choose Your Own Adventure" books, Jason Heller makes an interesting observation about the human response to choice:

As hooked as I was when I was 8, I didn’t stick with CYOA for long. By the time I was 10, I was getting into videogames and Dungeons & Dragons. Maybe CYOA helped prepare me for those pastimes, in which the choices were usually far more subtle and complex, even in those early days of gaming. The funny thing is, the older I get, the less enamored I am of choice. It’s no longer a novelty or a rite of passage to pick what I want to eat or watch or read or buy or vote for. Often it’s a chore—or, at worst, a source of mild anxiety. What once seemed like agency is now just another thing to worry about. The thought of going on some daring escapade across the globe doesn’t make my pulse pound. It makes my head hurt.Choice, as such, is often held to be the Holy Grail of human possibility. It's the be-all and end-all, in a "Give me liberty or give me death" sort of way. If we perceive ourselves to "have choices," we feel free and alive. If we perceive ourselves to be without choice, we feel trapped and dead. Heller's best line, at least to my ear, is when he says that, "what once seemed like agency is now just another thing to worry about." Why should this be? Shouldn't "agency" (the ability to choose our adventure) be the everyone's most precious desire?

What Heller's claim belies is a startling fact: we don't use our agency very well! Luther is said to have responded to someone's claim that their will was free by quipping something along the lines of, "Sure, you're free to make any bad decision you like." That's the reason that agency turns into a headache as we age. As our agency is used for more important things (the transition, say, from deciding what kind of juice to drink to deciding what job to take) we realize all the more how bound we are to mess up.

This, ultimately, is why a reduced view of human agency (free will) is good news. It posits a God that intervenes in our affairs, not waiting for us to make good decisions (e.g. choosing to follow and serve him), but making good and saving decisions on our behalf. In the drama of real life, God is the actor, we are the audience. Christ is the savior, we are the saved. Our agency works itself out in action that is bound in one way or another: the attempt to please someone, to achieve something, to get somewhere. More often than not, we don't make it. God’s agency cuts through our bondage, carrying us over the wreckage of our bound decision-making by his un-bound, free love in Christ. Choosing our own adventure seems like the way life ought to be, but it leads inevitably (as anyone who has read those books knows) to cataclysm, fear, and despair. It is only God's finished adventure in Christ that leads to relief, rest, and restoration.

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

The Squelched Swan Song of Tim Tebow

There appears to be a consensus forming that Tim Tebow's career as a football player is over. This, in itself, is a strange phenomenon, since he has a winning record as a starting quarterback in the NFL, a relatively rare achievement for a young player who came into the league with questionable talent and playing for a mediocre (at best) team. Heck, it's rare for any young quarterback to come out of the gate with a winning record. In any event, people have begun to speculate about what Tim Tebow might do next, now that he has no future in sports proper.

As has been well-reported in this (and every single other) space, Tim Tebow is a no-foolin' Christian, and one of the career options that is open to him is Mainstay on the Inspirational/Motivational Public Speaker Circuit. Tebow could likely earn his weight in gold dubloons each year, speaking to one packed stadium of Christians after another. But it might not be that easy.

Recently, Tebow accepted an invitation to speak at First Baptist Church in Dallas, the church led by Robert Jeffress, who has had some not-so-nice things to say about some segments of the population. Outcry was quickly and loudly heard. How could Tebow endorse Jeffess' message by agreeing to speak at his church? After some thought, Tebow cancelled the engagement, saying that he "needed to avoid controversy at this time." Outcry was quickly and loudly heard. How could Tebow bend his faith to the will of the politically correct establishment?

As ESPN.com's LZ Granderson says in his piece on this recent Tebow miasma, "Tim Tebow simply can't win." He's criticized for agreeing to speak and then criticized for what he doesn't say. We've touched on this before in relation to LeBron James and his "unwinnable" All-Star game last year. This Tebow story makes it clear: it is life itself that is the un-winnable game.

Jesus' Sermon on the Mount (as a window into his larger worldview) makes life un-winnable. We think we can defeat adultery, but must admit defeat to lust. We think we can defeat murder, but must admit defeat to anger. We think we can defeat the inability to love our neighbor, but must admit defeat to the requirement to love our enemies. God's first word (law, requirement, standard) is a defeating word. It shows us that no matter which way we go, left or right, toward First Baptist Church or away from it, we can never truly do what Jesus would do. WWJD is too tall an order. We must rely on God's final word (grace, love, forgiveness), which is an enlivening word. It's even better to say that God's word of law is a killing word. It destroys us, no matter what we do. God's word of grace, though, is a resurrecting word, bringing life out of death and glory out of defeat.

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

In Good Company on the Last Rung of the Ladder

Are you doing well as a Christian? It seems that, often, Christians are less concerned with the fact that they're a Christian than their proficiency at being one. Because of this, we envision our Christian lives as being like a ladder we have to climb. Sure, we think, Christ's great sacrifice for us was enough to get us on the ladder, but now it's up to us to move higher. We imagine Billy Graham and Mother Teresa as being very high on the ladder and those people who never read their Bibles or pray as being very low. This schema makes sense to us, and it allows us to do one of our favorite things in the world: compare ourselves and our progress to that of others.

So what, then, are we to make of the Great Christian Tumble? You know what I mean: when a great Christian (usually an evangelical leader, pastor of a giant church, or politically active preacher) is revealed to have been engaging in reprehensible behavior. We are immediately thrown into confusion; we don't know how to classify the event. Is this evidence that this person wasn't as high on the ladder as we had imagined? Perhaps they'd never really gotten on the ladder at all (i.e. they weren't really a Christian after all). The truth, though, is more profound, and right out of The Matrix: there is no ladder.

Check out this scene from the under-appreciated 2004 film In Good Company. Topher Grace has just gotten a big promotion at work, and he's in the mood to celebrate:

Isn't this just the way life works? Just when we feel we've gotten everything together, when everything seems to be going our way, it all falls apart. The same might be said of those Great Christian Tumblers. It's right when they're on top of the world that everything goes to hell.

I've said before that I'm ready to accept the ladder image of Christian growth as long as we can agree that the ladder is of infinite height (since we can never be perfect) and that, as we climb, each rung disappears beneath us (so that we're always on the last rung, hanging by our fingertips). This is the only way the Christian Ladder can be reconciled to human experience! But, like I said above, the truth is that there is no ladder.

Each of us are, as Martin Luther said, at the same time justified and sinner, or, in other words, we are both Christian and human. We live our lives in the glory of the Holy Spirit (Grace getting promoted) even while we are getting in accidents, getting called names, and getting abandoned by our loved ones. Our desperate need never goes away. The Book of Common Prayer, during the Ash Wednesday service, says that this nature of our lives puts us "in mind of the message of pardon and absolution set forth in the Gospel of our Savior, and of the need which all Christians continually have to renew their repentance and faith."

Truer words were never written. In ourselves, we are left in a crumpled heap at the bottom of the Christian ladder. In Christ, we are carried directly to the top, no work necessary on our part. Christ comes specifically for the accident prone, for the derided, and for the abandoned. That's a good thing, because that's where we live.

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

"Oh, Cutting Your Eyeball with a Laser-Knife is Totally Fine:" Casuistry and PEDs

Casuistry is a fancy theological word that means something like "the search for special cases." It exists by necessity; the law abounds, and so we humans (born lawyers, according to a friend) are compelled to search for ways to get around it. In fact, one might argue that casuistry makes up the bulk of a lawyer's job description: a client is accused of some manner of law-breaking, and the lawyer attempts to find a reason that, in at least this one instance, the law-breaking was justified. Lawyers spend dozens of billable hours a week at this job, but we humans are at it during every waking moment.

There are a million examples of casuistry in the world: lying is wrong...unless it will hurt someone's feelings. Stealing is wrong...unless it is from a big, faceless corporation. And now, a relatively new one: enhancing your performance on the athletic field is wrong...unless you do it in socially acceptable ways.

Syringes of Testosterone Cypionate, bad. Platelet-enriched ankles, good. The "cream" and the "clear," bad. Lasik surgery, good. Certainly it is true that some substances and procedures are banned by athletic federations and some are not, but the entire enterprise of picking and choosing which methods of performance-enhancement are "okay" and which are not is fraught with intellectual danger, if not outright buffoonery.

We engage in the casuistic exercise because we are desperate to justify ourselves. If we find an instance in which we are out of line (and therefore not "justified"), we scramble for a reason. "I told her that she looked great in that dress because the conventions of society told me to." "I didn't claim that income on my tax return because it would have required a lot of paperwork and it was only like $5 over the minimum limit anyway." Casuistry comes from the desire to never have to throw oneself on the mercy of the court and beg for a savior. Casuistry is a problem, then, for the same reason that anything that keeps us self-reliant is a problem: it clouds our ability to see ourselves as profoundly in need.

The more (seemingly) successful we are in our casuistic enterprise, the longer we will hold on to our (apparent) ability to save ourselves. But this is a ruse, a fake. We are in the Star Wars trash compactor, and the walls are closing in. Making up reasons that our situation is tenable is not a long-term solution. Best to shout out for help now.

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

Royce White on the Human Condition

Royce White is a great basketball player. He led his Iowa State team in every major statistical category as a sophomore and was a lottery pick in last year's NBA Draft, all while suffering from a serious anxiety disorder. He's currently in the throes of trying to work out a mental health protocol with the Houston Rockets (the team that drafted him) so that he can feel comfortable playing. White was recently interviewed by Chuck Klosterman for Grantland.com, and had some very revealing things to say.

CK: Well, then what's the lowest level of mental illness? What is the least problematic behavior that still suggests a mental illness?

RW: The reality is that you can't black-and-white it, no matter how much you want to. You have to be OK with it being gray. There is no end or beginning. It's more individualistic. If someone tears a ligament, there is a grade for its severity. But there's no grade with mental illness. It all has to do with the person and their environment and how they are affected by that environment.

CK: OK, I get that. But you classify a gambling addiction as a mental illness. Gambling is incredibly common among hypercompetitive people. The NBA is filled with hypercompetitive people. So wouldn't this mean that —

RW: Here's an even tougher thing that we're just starting to uncover: How many people don't have a mental illness? But that's what we don't want to talk about.

CK: Why wouldn't we want to talk about that?

RW: Because that would mean the majority is mentally ill, and that we should base all our policies around the idea of supporting the mentally ill. Because they're the majority of people. But if we keep thinking of them as a minority, we can say, "You stay over there and deal with your problems over there."

CK: OK, just so I get this right: You're arguing that most Americans have a mental illness.

RW: Exactly. That's definitely correct.

CK: But — if that's true — wouldn't that mean "mental illness" is just a normative condition? That it's just how people are?

RW: That doesn't make it normal. This is based on science. If there was a flu epidemic, and 60 percent of the country had the flu, it wouldn't make it normal.

White has hit on something here, something that Christians have always known. Despite Klosterman's seeming confusion, what White is talking about is an idea as old as Christian theology: original sin. Humans all have a problem, and even though it's spread evenly throughout the entire population, it's still a problem. In other words, it's normative and problematic.

We like to think that it's mostly those "other" people who have a problem. As White says, it comforts us to be able to shunt them over to a corner to deal with the problems that we claim we don't have. This is the tragic genius of Jesus' Sermon on the Mount: he takes all our problems back to first principles (it's not murder, it's anger; it's not adultery, it's lust; and so on) tearing down our ability to think ourselves "illness-free."

The church should look like Royce White's America: he would have us "base all our policies around the idea of supporting the mentally ill." Our churches should base all their policies around the idea of supporting sinners by proclaiming the arrival of a Savior.

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

A Ray Lewis Redemption

I find Ray Lewis' persona, both on and off the field, to be oppressively distasteful. He seems boastful, showy, and hugely self-absorbed. Exhibit A is his presence on the field for the final snap of the Ravens victory against the Broncos (his final home game) to facilitate his signature "look at me" dance. The final snap was a Ravens offensive kneel-down; Lewis is a defensive player. Despite all of this, I'm almost disappointed that he's retiring after this season, because the consensus is that he'll be a "great" television announcer, which means I'll just be subjected to more of him after his retirement than I was before it.

Also, there's the fact that he lied to police in an attempt to impede a murder investigation, and investigation in which Lewis himself was implicated.

For many years, I used this information to justify my hatred of Lewis. Sure, some of that hatred comes from the fact that I'm a Steelers fan, and Lewis is one of our nemeses. Some of it comes from his self-aggrandizement. But a lot of it comes from my belief that he's a criminal, who got away with a plea-bargain. These feelings came to the surface again several years ago during the national discussion about whether or not Michael Vick (convicted of running a dog fighting operation) should be allowed to play in the NFL again. It angered me that Lewis, present and potentially complicit in the death of a human being, was never so much as suspended, while there was sentiment that Vick shouldn't ever be allowed to play again.

The truth about Ray Lewis is this: he made a bad mistake. Very, very bad. He's not unlike me. But I need him to be unlike me.

My ability to feel good about myself requires people to exist in the world who are worse than I am. Ray Lewis fills that role. In Nick Hornby's book How to be Good, his heroine (a doctor) is a better person than her husband. One day, though, her husband experiences a spiritual conversion, and becomes (for the purposes of the book) "good." All of a sudden, the wife's world and identity are thrown upside down. She has defined herself as being "better" than her husband...now that she isn't that, who is she?

If I can't say that I'm better than Ray Lewis, who am I? What value do I have?

Ray Lewis, by all accounts, has completely reformed his life since the incident in 2000. He is a devout Christian, a pillar of his community, and a mentor to many young men. His is a story of redemption, and such stories are what we, the redeemed, should be cheering. I may not be better than Ray Lewis, but that's not a bad thing. We share an incapacitating compulsion to selfishness and sin, and we share in a regenerating love of a Savior infinitely better than both of us.

Oh, and one more thing: I hope Ray Lewis and his Ravens get crushed on Sunday.

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Why I Like that RGIII is called "Black Jesus"

I could have called this post "I Literally Couldn't Think of One Original Thing to Say About Manti Te'o," but that seemed a little wordy...and, you know, uninformative. Seriously, though, I just flew in from Chicago and boy are my arms tired! One word, though, about Te'o before we move on. It seems to me that this whole story (a story about which, amazingly, we still don't have all the facts) shines a light on one universal human truth: we will do (or believe) absolutely anything if we feel that we are beloved. I mean, Te'o allegedly flew to Hawaii just to see his (non-existent) girlfriend, and even though she proceeded to only communicated with him via text on that whole trip, he still "wasn't sure" whether or not she existed until a week ago! "She" even, at one point, asked him for his checking account number! However, she also said that she loved him. Who among us wouldn't do anything for such a woman?

Now, on to Black Jesus. Robert Griffin III is not the first athlete to be dubbed "______ Jesus." Most receive the moniker for their on-field exploits (Larry Bird, the "Basketball Jesus"), although Charlie Whitehurst is called "Clipboard Jesus" more for the look (and for the fact that he never plays). My question is, do we have to wait for Andy Dalton to win a Super Bowl before he's dubbed "Ginger Jesus?" In any event, the appellation rubbed me the wrong way at first, as you might expect. But did you catch Fred Davis' explanation for the nickname (in the above linked article)? "I mean, like I said, he's Black Jesus right now. He saved us today."

Whatever hesitation I have about the name of the Christ being invoked so flippantly is mitigated by the fact that the people who are using it are at least thinking in terms of Jesus as a savior. This is rare enough to be remarkable (and important). Normally, for people both Christian and non-, Jesus is nothing more than exemplar of love, care, and charity. He is the classic "great moral teacher" to whom C.S. Lewis refers. Fred Davis, though, is thinking of salvation. Robert Griffin III saved the Redskins, and Jesus saves us. The defense rests: Black Jesus.

It's helpful to look at this from the other side. As I've said, most people see Jesus primarily as an example to be followed, in the same way that all of the New England Patriots have adopted coach Bill Belichick's "mum's the word" press conference style. No one, however, has ever been (nor will ever be) moved to refer to Belichick as "Podium Jesus."

So let's call Robert Griffin III "Black Jesus." Anything to keep All-of-Creation Jesus' saving work in the front of our minds.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Lance Armstrong Redeems...Lance Armstrong?

As I write this (Wednesday, January 16), Oprah Winfrey has confirmed that, in an exclusive interview taped on Monday to air on Thursday, Lance Armstrong has admitted to the use of performance enhancing drugs. At this point, this is a total snore. With the baseball writers' recent decision to not vote a single player into the Hall of Fame (some simply for the possession of bacne), PED accusations and confessions are like Beanie Babies: when everyone's got one, no one cares.

The Wall Street Journal (online) has a piece in the January 15 issue called "Behind Lance Armstrong's Decision to Talk" which attributes a quote to the athlete, and a response by a bureaucrat, that is decidedly not a snore. In a meeting with Travis Tygart, the head of the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), Armstrong pointed to himself and said,"You don't hold the keys to my redemption. There's one person who holds the keys to my redemption, and that's me." We've covered this human desire before (most specifically HERE), but the fascinating thing about this quote isn't the brazenness; it's the common nature of the refrain.

Everyone thinks that their redemption is up to them. Except, maybe, for Travis Tygart. Upon hearing Armstrong's claim, Tygart allegedly responded, "That's b-[expletive]." Now Tygart seems to have simply been calling bull-waste on Armstrong's allusion to redemption in any form, claiming that the cyclist would do and say anything to be allowed to race again. But his initial reaction is accurate. The idea that we hold the keys to our own redemption is total b-[expletive].

That Armstrong might believe that baring his soul (or, at least, the contents of his medicine cabinet) to Oprah would lead to his redemption is, at worst, cynical in the extreme and at best, evidence of a woefully weak definition of redemption.

When Christians talk about redemption, we don't refer to a return to a prior state of good standing. Some do, actually, but such thinking, as Gerhard Forde points out in his seminal On Being a Theologian of the Cross, hinges on the un-Biblical notion of a "Fall." We imagine that we were once at a certain place in our relationship with God, we messed that up, and Jesus gives us the ability to get back. That is, according to Forde, "a tightly woven theology of glory [a theology that "uses" Jesus and the cross to "get" us something, rather than one that sees Jesus and the cross as the end of us, and our resurrection]." The truth is so much better. In our redemption (in real redemption) we are saved to a state higher than we ever had before: we are regarded as one with Christ, as God's own son.

If that is the gift, then we cannot hold the keys. And thank goodness, too, because when another (a saving Christ) holds them, our gift is immeasurably more valuable.

Friday, January 11, 2013

The Problem with Perfection

On April 12, 2012, Philip Humber (who had never pitched through a full eight innings of a major league outing) pitched a perfect game. That is, he retired 27 batters in a row, three up and three down, every inning for nine innings. No walks, no hits. Only eighteen other men in the 108-year history of Major League Baseball have accomplished the feat. In November of that same year, the White Sox cut him, making him available to any team in the league. What happened?

In an interview with Sports Illustrated's Albert Chen (December 31, 2012), Humber tried to explain it. Check out how the article is subtitled: "For one magical April afternoon, Philip Humber was flawless. But that random smile from the pitching gods came with a heavy burden: the pressure to live up to a standard no one can meet." Unfortunately, though whichever editor wrote that subtitle is ultimately correct, we use examples like Humber's to delude ourselves. "But he did throw a perfect game," we say. "Perfection is possible." Our desire to be perfect is so strong that we willfully ignore the headline's larger point: that true perfection in only achieved by throwing a perfect game again. And again. And again.

The ladder of perfection has no top rung. There is no platform upon which we can finally rest. Whether our goal is to be a good father, a good Christian, or a good pitcher, each exemplary act carries with it the expectation (the requirement) of another. And another. "Being like Christ" is not like throwing a perfect game. Living up to the Sermon on the Mount is not like throwing a perfect game. Being a caring husband is not like throwing a perfect game. They are like throwing perfect games every day of your life...while never being proud of the fact that you're throwing perfect games! Remember, don't let your left hand know what your right hand is doing (Matt 6:3). A perfect game in the game of life is impossible, but is required nonetheless (Matt 5:48). So we buckle down.

Every time Humber took the mound, he tried to be the pitcher he was in Seattle-but competence seemed unattainable, much less perfection. In his next start, he allowed nine runs in five innings. Two outings later he was bombed for eight runs in 2 1/3 innings. Every time he fell short of the new standard he set for himself, he pushed himself harder. He began spending more time than ever in the video room. He played with every imaginable grip for his pitches. He threw extra bullpen sessions. He ran more, lifted more. He asked teammates how they dealt with their struggles. He couldn't understand why he couldn't recapture the magic. "I just feel lost," Humber said to [pitching coach Don] Cooper at one point. "I don't know what I'm doing out there."The quest for glory, the chasing of perfection, killed Humber's season. He never regained the form that mowed down all those Seattle Mariners, and the White Sox eventually gave up on him. In order to move on, Humber had to give up:

Is this the end? The beginning? Philip Humber doesn't know what will come next in his baseball story. This he knows: He's done chasing perfection. He's done trying to be the pitcher with the magical fastball and the unhittable slider. He knows he's a 30-year-old pitcher with a fading heater and a curveball that doesn't bite like it once did, and he accepts that. He also thinks that he's a wiser pitcher who can still win games for a major league team. "Next time I throw a perfect game," he likes to joke, "I'll know how to handle it better."Philip Humber came to grips with his limitations...the truth about himself. He's been signed by his hometown Houston Astros for next season and seems to know that, in order to be a good pitcher, he has to let perfection go. Let's remind ourselves daily, hourly, and by the minute, that we can let perfection go, because it is a mantle that Christ has taken up for us.

Wednesday, January 2, 2013

Go Big This New Year

So it’s time for resolutions again. Each year, we make commitments to ourselves (and others, and even, perhaps, to God) to be better than we were last year. Perhaps we want to finally lose that pesky fifteen pounds. Or fifty. Or we want to be more faithful in our Bible-reading and in our prayer lives. We want to finally put aside that besetting sin that’s been plaguing us. A new year seems a good time for a fresh start.

I’ve never made resolutions, but for years, it was only because I knew I had no hope of actually keeping them. In fact, hasn’t joking about breaking your resolutions become more of a habit than the resolution-making itself? Recently, my problem with resolutions has become more theological in nature. I envision St. Paul waking up on January 1, noticing all his Facebook friends’ resolutions, and posting something along the lines of Galatians 3:

“O foolish [people]! Who has bewitched you, before whose eyes Jesus Christ was publicly portrayed as crucified? Let me ask you only this: Did you receive the Spirit by works of the law, or by hearing with faith? Are you so foolish? Having begun with the Spirit, are you now ending with the flesh? Did you experience so many things in vain? Does he who supplies the Spirit to you and works miracles among you do so by works of the law, or by hearing with faith?”

We Christians have been given an eternal answer for the gulf that exists between the “us” that we are and the “us” that we ought to be: “All sinned…and are justified freely as a gift by the redemption that is in Christ Jesus” (Rom 3:23-24). But the way we talk about resolutions often sounds like an attempt to, as Paul put it in Galatians 3, “finish in the flesh.” “The righteousness of God has been revealed apart from the law,” says Romans 3:21, and yet we take New Years as our chance to make a new law, the law of the resolution.

So my answer used to be: Don’t make resolutions. You’d be foolish to live under a law, knowing how the law works, and knowing that it necessarily results in death (cf. Rom 7:11). This year, though, I’ve got a new idea: make your resolutions harder.

The problem with your resolutions isn’t that they’re too hard for you to keep (though they usually are). The problem is that you think you’ve got a chance. So you rely on yourself, work up your will, exert all your effort, and give it your best shot. We think, perhaps, that we can shrink, by our striving, that gulf between the “us” we are and the “us” we ought to be and, just maybe, one day get across.

When John the Baptist is continually questioned about his standing with regard to Jesus, he finally says that Jesus “must become greater, and I must become less” (John 3:30). In other words, we should increase our need for Christ, rather than work to decrease it. Our resolutions should look less like a register of achievable goals and more like the demands of Matthew 5:17-48: a terrifying list of requirements that force us to our knees. We should know, looking at that gulf between our selves, that, should we attempt to jump it, we would surely be dashed to pieces on the rocks below.

We attempt to tell ourselves that a happy new year is one in which we get closer to other side of that divide, if not finally reach it. A truly happy New Year, though, is one in which we come face to face with our need for a savior and hear the Good News proclaimed: not only has our savior come, but he has done his work, and brought us out of error into truth, out of sin into righteousness, and out of death into life.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)